You are ready to hire your first sales leader when you are prepared to buy leverage, not relief. Titles do not grow revenue. A high-impact sales leader creates durable selling capability, reduces owner dependency, and raises standards through coaching, recruiting, and operating cadence. If what you really want is a second version of you to carry the number and keep deals moving, you are hiring a band-aid, and you will pay for it twice.

Most owners make this hire at precisely the wrong moment. The pressure is real, the pipeline feels fragile, and the business is starting to outgrow informal management. So the owner reaches for the obvious move: “We need a sales manager.” The problem is that the role is designed around short-term comfort rather than long-term capacity. The result is a well-paid administrative firefighter who inherits the chaos instead of fixing the system that creates it.

Before you post a job, clarify the objective. Do you want a revenue driver or a capability builder?

A revenue driver is a manager who helps you hit the number by conducting deal inspections, applying forecast pressure, and holding reps accountable. That can be valuable, but it is often a disguised need for personal production. A capability builder is a leader who creates repeatable performance by improving the quality of selling, tightening hiring standards, and building a coaching system that makes average reps better and good reps consistent. That is the role that changes enterprise value.

Here is the hard truth most owners avoid. If you design a role that combines selling and leading, selling will win. Always. When a leader has a quota, the business trains them to prioritize their own deals over the team’s development. They will “help” reps when a deal is in a late-stage, visible phase, then postpone coaching, recruiting, and onboarding because those activities do not pay this month. Over time, the team remains dependent, the pipeline remains uneven, and the owner remains in the middle.

Assessing readiness: leader or band aid

Readiness is not a revenue threshold. It is an operating decision. The question is whether you will let a sales leader lead.

The owner’s trap is hiring a leader while keeping day-to-day control: still running reviews, intervening in pricing, rewriting emails, jumping on calls, and closing important deals. In that environment, the new leader cannot build authority; they become an assistant with a title. You’ll be frustrated they’re “not taking enough off my plate,” while they’re frustrated at not being able to make decisions without you.

If you want a clean test, look for these warning signs:

- You are still the primary deal closer and default problem solver.

- You do not believe the company can make the number without your direct involvement.

- You step into deals because you do not trust the process, the rep, or the forecast.

- Your coaching is ad hoc, usually when something goes wrong.

- Recruiting is episodic, triggered by pain, rather than continuous.

If several of these warning signs are true, you are likely seeking relief, not leverage. This does not mean you should never hire, but be clear that the first sales leader is not a shortcut. Rushing the hire creates a role that absorbs noise, running meetings, change updates, and CRM hygiene, without driving real improvement.

A sales leader is most valuable when the business is ready to standardize what “good” looks like and enforce it consistently. That requires the owner to relinquish control of day-to-day execution while remaining accountable for outcomes. Many owners say they want that, then undermine it the first time a big deal wobbles.

The risks of poor role construction

Two standard constructions fail in predictable ways. They fail because they violate the purpose of leadership.

The “sword” of promoting your top producer

Promoting your best rep feels like a safe bet. They know the product, they know the market, they have credibility, and they “get it.” The issue is that selling excellence and leadership competence are different capabilities. A top producer wins through personal patterns, not transferable systems. They may be great at reading buyers, improvising in discovery, and navigating politics. That does not mean they can coach others, recruit talent, or enforce standards without playing favorites.

The risks are tangible and measurable:

- You often lose top-tier production immediately.

- Culture degrades because the new manager keeps selling informally, picking up accounts, and sending the signal that the path to status is through personal heroics.

- Coaching becomes advice-giving, not skill-building. Reps get tactics, not operating discipline.

- Performance becomes inconsistent because the leader never builds a team system; they just try to “help” everyone close.

This is why the promotion can be a sword. It cuts both ways. You sacrifice your strongest revenue engine and still do not get leadership.

If you promote internally, do it with eyes open and a plan. The decision is acceptable when the person has demonstrated coaching behavior, recruits without bias, and leads without needing the spotlight. Otherwise, you are paying for hope.

The player-coach trap

The most common mistake is requiring the first sales leader to carry a personal quota. Owners justify it with economics. “We cannot afford a manager who doesn’t sell.” That sentence is usually a signal that the business is not ready to hire a leader; it is ready to add a senior rep.

When the sales leader is a seller, coaching becomes optional. Recruiting becomes a quarterly project. Onboarding becomes a checklist. Forecasting becomes pressure. Everyone ends up looking at the leader’s number rather than the team’s operating health.

The long-term consequence is simple. You freeze the organization at the stage where everything depends on a few strong individuals. That is the opposite of scale.

If you need the person to produce to make the math work, you are buying revenue. Call it what it is and hire a seller. A production-focused leadership role is a mislabeled individual contributor role, and it will disappoint you.

Designing the high-impact role

A real first sales leader’s schedule should reflect their purpose. They are there to raise others’ performance, not to be the most talented rep in the room.

Coaching and recruiting must dominate the calendar. Administration supports those two priorities. Production is either zero or transitional, with hard limits.

Here is a practical time allocation that holds up in the real world:

Coaching: 40 to 50 percent

This includes weekly one-on-ones, call reviews, deal strategy sessions focused on thinking, and live observation, such as ride-alongs or recorded calls. Coaching is not a motivational talk. It is skill development tied to standards. It should be specific, behavioral, and measurable.

If the leader is not spending almost half their time in coaching activity, they are managing, not leading. Your team will receive oversight and minor improvements.

Recruiting: 25 to 30 percent

The leader owns a constant pipeline of talent. That means sourcing, interviewing, using scorecards, and maintaining consistent standards. Hiring is a system, not an event. The first sales leader who treats recruiting as ongoing work will save you from the most expensive problem in sales: carrying the wrong people too long because you do not have better options.

Admin and management: 15 to 20 percent

Forecasting, CRM discipline, pipeline inspection, compensation administration, and basic performance tracking fall under this category. These activities matter, but they are supportive. When the admin expands to fill the role, it will. Your leader will be busy, and your team will stay mediocre.

Producing: 0 to 15 percent

If producing exists, it should be clearly transitional, clearly time-boxed, and structurally limited. For example, they may carry a small book of renewals for 90 days while a rep is hired, or they may close a few legacy deals to protect a fragile quarter. The key is that producing cannot become their identity.

If personal production accounts for more than 20 percent of their time, the role is failing. You have hired a seller with management duties. The business will get short-term help and long-term stagnation.

Role design also needs decision rights. If you hire a leader but retain pricing, hiring, or deal-approval authority for yourself, you undermine the leader’s effectiveness and risk creating decision bottlenecks. This makes it difficult for the leader to own outcomes fully and discourages proper accountability. Decide what they own, then allow them to exercise those rights.

Measuring success in the first year

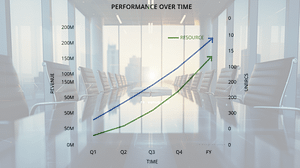

The wrong metric for a first sales leader is “How much did they sell?” The right metric is “How much leverage did they create?”

Leverage shows up as improved team performance without increased owner effort. It shows up as predictability. It shows up as standards that hold when the leader is not in the room.

A simple first-year scorecard includes:

Consistency in rep activity

Look for stable inputs: prospecting volume, meeting creation, follow-up discipline, and opportunity progression. A leader should establish a cadence in which the right activities occur without drama. When activity is consistent, results are easier to forecast and less dependent on heroic efforts.

Faster onboarding and ramp time

New hires should reach competence more quickly because the leader provides an absolute onboarding path, clear expectations, and regular coaching. If ramp time stays the same, the leader is managing reports rather than building capability.

Decreased owner involvement in individual deals

This is one of the cleanest indicators. Track how often you join calls, intervene in pricing, or get pulled into deal rescue. Your involvement should drop quarter over quarter. If it does not, either you are not letting the leader lead, or the leader is not building rep independence.

Establishment of a talent bench

The business should have a visible pipeline of candidates and a clear profile of what “good” looks like. The leader should also develop internal bench strength so future promotions are earned rather than forced by growth.

None of these KPIs is fluffy. They translate directly into enterprise value. A company that can grow without the owner in the middle of every deal is a company that can be scaled, sold, or delegated with confidence.

Strategic alternatives and the final gut check

If you are not ready for a full-time sales leader, you still have options. The worst option is pretending you are ready and making a bad hire that takes a year to unwind.

Start with a readiness test that forces honesty:

- Am I willing to stop being the default closer, even when a big deal is at risk?

- Do I have a defined sales process and standards that I will enforce, even when it is uncomfortable?

- Do we currently coach weekly, or do we only discuss deals when something goes wrong?

- Do we recruit continuously, or only when we are in pain?

- Will I give this leader fundamental decision rights over hiring, coaching cadence, and operating rhythm?

If you cannot answer these with a clean yes, you are not wrong. You are early. Treat it that way and intentionally bridge the gap.

For many businesses, a fractional sales leadership approach is the right bridge. A seasoned leader can build your coaching cadence, implement the hiring system, define standards, and establish an operating rhythm at a lower cost than a full-time hire. More importantly, fractional leadership can reduce owner dependency without forcing you into an all-in salary decision before the business has earned it.

Used correctly, fractional leadership does three things:

- Stabilizes execution through a consistent cadence of coaching and inspection.

- Builds the recruiting engine so you never hire out of desperation.

- Prepares the org for a full-time leader by clarifying the role, metrics, and decision rights.

That bridge matters because the first full-time leader should step into a role designed for leverage, with apparent authority and a defined operating system. Otherwise, you are asking them to invent the job while carrying the emotional weight of your expectations.

The bottom line is simple. A successful sales leader multiplies others’ capabilities rather than doing the work themselves. If you are ready to buy that leverage, design the role around coaching and recruiting, grant authority, and measure success by reducing owner dependency and improving team performance. If you are not ready, choose the bridge that builds the machine before you hire the person to run it.